On Reluctantly Deleting the Oxford Comma

Am I among those who have posed for an Instagram pic with my new hardcopy Associated Press (AP) Style Guide like a total dweeb? One of those persistently obnoxious people on your Facebook feed who posts her scores on online grammar quizzes? A constant corrector of grammar and pronunciation, even over drinks at the bar?

Friends, clients, coworkers, countrymen: I am.

And don’t let that lead graph fool you into thinking I’m at all self conscious about it. You probably know a writer or proofreader who shares the same smugness about all things grammar and style. (Do find every opportunity to point out this person’s own proofreading foibles; we really do need to be knocked off our high horses.)

However, I humbly submit that myself and my fellow MGH PR practitioners, as well as writers and readers all over the world, are this way for a deeper reason than the joy of correcting others: It matters. It makes a difference. Clarity is the holy grail of communication, and we’re just trying to make sure that those who read our press releases, wave to our billboards and react to our digital ads know precisely what our clients are trying to communicate.

So we, like PR pros around the country, are devotees of the AP Style Guide. Most major publications hew more or less to the foundational elements of AP Style, although each certainly has its variances. (Don’t even get me started on The New Yorker’s strange style mandates.) Our job is to give journalists clear, easy-to-understand information. It follows that we’d try to use the same style guide journalists do. (Unless it’s the New Yorker, in which case we’ll need to scour the internet for a way to produce diaereses in Microsoft Word.)

But that doesn’t mean we agree with all the AP Style Guide’s rules. In the name of clarity, here are a few that even our toughest MGH proofreaders agree could use a revision:

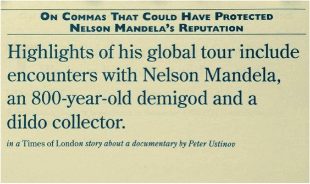

- The Oxford comma. Also known as the serial comma, this comma comes before the word “and” and the end of a list (or series). I’ll let a handy graphic do all the talking about why, for clarity’s sake, the AP needs to adopt the Oxford comma badly. (Don’t just take the graphic’s word for it – CNN reported last week on a court case determined by the absence of an Oxford comma.)

- State abbreviations. Most people use postal abbreviations to denote states: MD for Maryland, CA for California, NV for Nevada and so on. Not so, says the AP. You’ll have to use Md. for Maryland, Calif. for California and Nev. for Nevada. Eight states with short names cannot be abbreviated, ever. Think Texas, Ohio, Idaho. We call BS on this method being the clearer one – it tends to lend the appearance of inconsistency when, for example, Md. and Ohio are used in the same list.

- Numerals, ordinal numbers and percentage signs. AP Style has lots and lots and lots of rules about the use of numerals in various situations, but the most basic one dictates that writers should spell out numbers under 10 (one, two, three, etc.) and only use numerals for figures 10 and above. Similarly for ordinal numbers, anything below 10th has to be spelled out. And percentage signs are a no-no in copy. I don’t know about you, but it’s much easier for me to read “Less than 2% of respondents said…” than “Less than two percent of respondents said…” For those of us who do a lot of PR around research, these rules are overly restrictive and should often be skipped.

But hey, at the end of the day, we still love the AP Style Guide. Especially since it's adopted hipper lingo around all things digital. Typing out “Web site” and “e-mail” was starting to get painful.